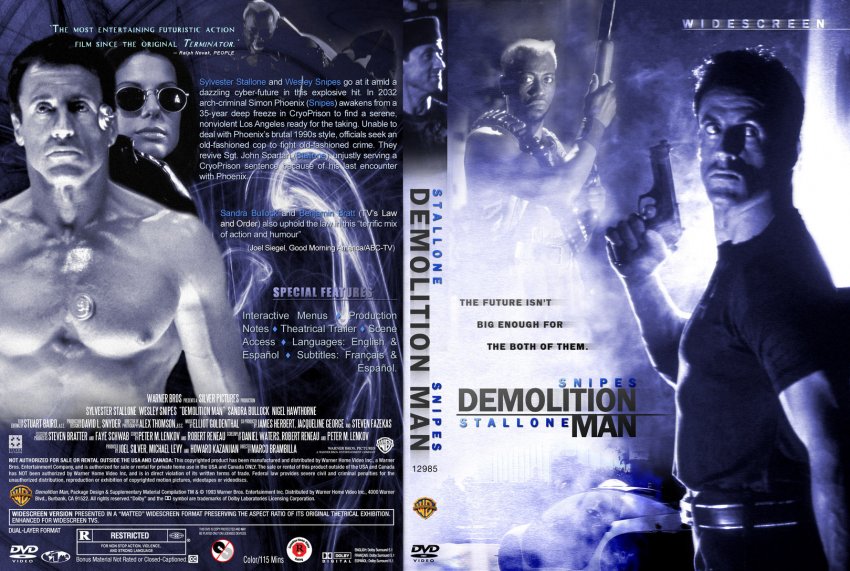

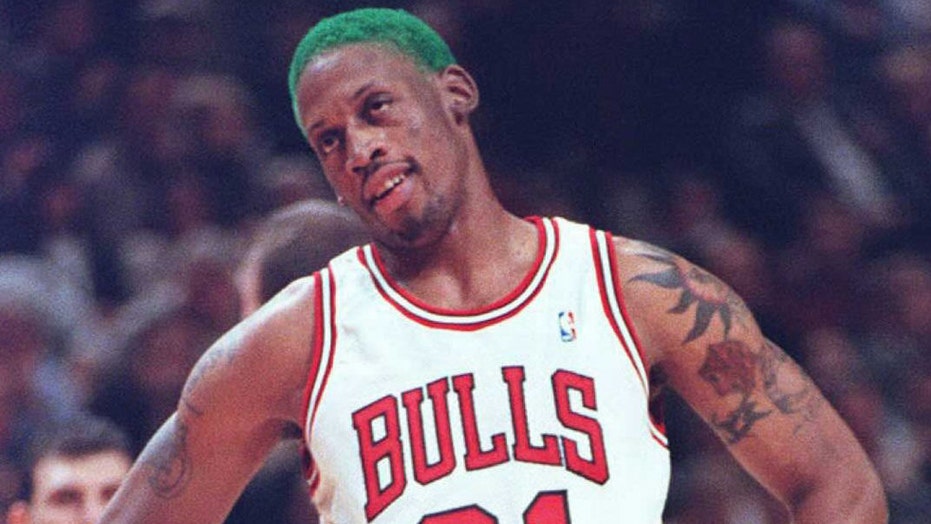

Then Stallone signed on and the movie became, by default, a Sylvester Stallone movie, and much of that promise vanished instantly.Īfter the requisite set-piece in a futuristic 1996 where Stallone’s glowering super-cop Sergeant John Spartan (even his name screams “scowling block of granite”) tangles with crazy-haired Simon Phoenix ( Wesley Snipes), Demolition Man does something bold: it leaves Stallone’s protagonist offscreen for close to half an hour so that it can build out the future world of 2032 that is alternately utopian and dystopian. He’s also played Barney Ross, a mercenary with a heart of gold, in three The Expendables extravaganzas and resurrected the role of shattered warrior Rambo in the 2008 film of the same name.īefore Stallone experienced a revival by revisiting his best-loved characters, he stumbled through the 1980s and 1990s with projects like 1993’s Demolition Man, which radiated extraordinary promise as a smart, subversive, and loopy meta-meditation on violence in pop culture and the excesses of what was then known as political correctness, co-written by Daniel Waters of Heathers and Batman Returns fame. In the past 11 years, he played Rocky in 2006’s Rocky Balboa and then reprised the role in last year’s Creed. He’s not a chameleon who slips inside the minds of sharply different characters so much as he makes the same damn film, playing the same damn character, over and over again. Though he is an Academy Award-nominated thespian, Stallone isn’t really an actor. But Stallone’s subsequent unwillingness to delegate authority or compromise for the sake of someone else’s vision has made his more troubled films cautionary warnings about the dangers of actorly egos run amok rather than the show-biz fairy tale of Rocky. The story of how a struggling young actor named Sylvester Stallone refused to sell the script to Rocky for a small fortune unless he was cast in the lead is a cherished piece of Hollywood mythology.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)